Either way, marriage semiotics and engagement rings in particular clearly invoke different reactions from the men who purchase them, the women who wear them and the rest of the world that lays eyes on these signs every day. Rings, dresses and conspicuous weddings are context specific in their interpretations; some view them as religious, others view them as fantasy come to life and still others see them as a reminder that perhaps gender roles are not as advanced as we may have thought. Have women allowed their role as the sole wearers to empower them, or are they hiding meekly behind the “no trespassing” sign otherwise known as a Tiffany’s princess–cut ring? Does the club-like nature of fiancée circles reflect the power they hold or their insecurity and the weakness they embody when standing alone? The engagement ring has the ability to symbolize power, status and visibility for the fiancée in public spheres, but to the inquisitive eye it highlights the one-sided control bestowed upon men through the powerful acts of purchase and bestowal.

To further complicate this issue, what does it say when a woman breaks the mold of a quintessential fiancée and refuses to wear an engagement ring? In the harsh, modern days of divorce, pre-nuptial agreements and failing economies how has the role of the engagement ring changed? Stepping into the powerful, public sphere of life how do other men and women react to the sight of an engagement ring? In 1949 the rising popularity of the engagement ring was emphasized by the inclusion of the song “Diamonds Are a Girl’s Best Friend” in the new Broadway musical, Gentlemen Prefer Blondes. More than sixty years later, in a society plagued by ageism, rising divorce rates and a failing economy, Jule Styne’s lyrics seem more pertinent than ever: “but square-cut or pear-shaped/these rocks won’t lose their shape”. How do brides today use the visibility of their engagement rings to their advantage? From these questions I could see in whose hands the power lay, if power and gender roles have changed in the slightest over the past fifty years, or if like diamonds, certain things are “forever”.

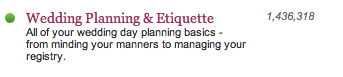

In The Human Condition Hannah Arendt describes the importance of publicity, visibility and the group dynamic in crafting a space for oneself in the world, “Power springs up between men when they act together and vanishes the moment they disperse” (Arendt 201). The most significant finding in my fieldwork pointed to the existence of a sort of “bridal club”, even an army. When acting together fiancées can claim visibility and attention from the external world as well as one another. The type of protection given by this group is inherent in it’s status and symbolism, especially that of the engagement ring. As Erving Goffman explains in The Presentation of Self in Everyday Life “Society is organized on the principle that any individual who possesses certain social characteristic has a moral right to expect that others will value and treat him in an appropriate way” (Goffman 13). Troops of fiancées, armed with diamond engagement rings demand respect, status and authority through their public visibility. Any strong army exudes a measure of sameness throughout their troops, whether it is country of origin, motivating purpose or a multitude of other factors. If one does not fit into the mold, it is not unlikely that one would be seen as the enemy. I found such to be true as I carried out my mediated fieldwork on popular bridal website, Brides.com. Although I made every attempt to fit in, my lack of experience both on the site and with my own engagement period caused me to be seen as an outsider:

“I began to see that perhaps my lack of experience and

establishment on the site was creating a divide between the

brides and myself… Public as the realm may be, its level of

exclusivity and the specific nature of topics with which its

members must be familiar, makes it just as private as any elite

group” (Fauxfiancee, 20 July 2011).

I began to see that in another way, the “bridal club” might be seen as a type of sorority in which a potential member must establish them self through various rights of passage in order to belong.

To become initiated in the “bridal club” one must succumb to the public displays of adornment otherwise known in American culture to embody the “dream wedding”: a sparkling ring, lavish wedding and other symbols of conspicuous consumption. What happens if a fiancée breaks the mold? They are not regarded as a member, and are seen through the eyes of the educated as the enemy, no matter if this is a fair judgment. Power begins with public appearance, and one must keep up appearances; fiancées are not the exception, they are the rule (Arendt 202). Throughout my experiences in the mediated world and the dress-up world – in which I pretended to be a fiancée to conduct ethnographic fieldwork – I gained insight that has led me to believe that those initiated into the “club” enjoy lifetime access. This is the only explanation I could find for women who returned to discuss engagement trivialities on the website or gush over my faux ring in public, despite having already been married for decades. Whether one is active in the sisterhood or an alumnus, the allure of the engagement period and the fantasy that revolves around can be indulged.

One might ask, why the desire for a married woman to return to (at least the ideals of) a period of engagement? It is clear, through the extensions of popular culture and fairytales that the period of being a bride realizes many women’s childhood fantasies. At last the ideal of Cinderella is attainable, if only for a day. It is here that I raise concern with these seemingly harmless fantasies. A woman’s wedding day should certainly be special, but should also be taken for what it is, an exciting introduction to a – hopefully – even more exciting period of life spent as a married woman. Unfortunately, many concerns rest upon that ‘hopefully’. The splendor and fairytale of a wedding is in fact a one-time occurrence – the fantasy will not be sustained everyday. Does the distraction and glamour of a fantasy wedding perhaps mask the fears and concerns fiancées have with the reality of marriage? Not surprisingly, the sparkle extends to re-attract wives as well as fiancées. In my mediated experiment I interacted with women who were married for up to 50 years, who created a profile online in order to give advice to women regarding their own weddings. These women seem to focus on the idea of another’s engagement period perhaps to relive their own, when their idealized self was more reality than fantasy. Years ago they were the best version of themselves: younger, more beautiful and thus more desirable, traits today that are mutually exclusive with age. Wouldn’t you then assume that this signifies some sort of dissatisfaction with married life? Perhaps the wedding was as anti-climactic as would be assumed with all the pressure resting on its perfection. Maybe a bride is treated as Cinderella for a day during her wedding, but by the rest of the public and not her groom. As I witnessed in my dress-up fieldwork, it is not only already married women who have an obsession with this intermediary engagement period, single women do as well. Through the marketing of “Fashion Rings” at stores like Nordstrom Rack, the idea and symbolism inherent in being a bride can be yours for the reasonable price of $14.12 (Fauxfiancee, 3 August 2011). Today it is seen as trendy, fashionable and yes, desirable to pretend one is experiencing this Cinderella moment for themselves. While perhaps women used to dream of the day in which they would be married, now the pageantry of merely wearing an engagement ring will suffice.

The tradition of bridal adornment was by no means recently established, yet it only reached its peak in the twentieth century. For centuries dowries and bride prices changed hands before a proposal was agreed upon; the groom would claim a dowry from the bride’s family, and in return the bride’s family would receive a “bride price” – to be clear, this went to her family and not her in particular. Although in the early days these exchanges consisted of livestock and land, they were later driven to become consumption heavy and reliant on adornment. Throughout the history of the engagement ring, many variations were utilized before settling on the popular diamond ring of today. Betrothal rings became popular in the 13th century Holy Roman Empire, and years later “regards” rings were given to a man’s fiancée adorned with her birthstone. The first appearance of a diamond engagement ring was in 1477 when Mary of Burgundy was asked to marry her Austrian beau. Despite this introduction, diamond rings were not commonplace until the 19th century when miners discovered diamonds in South Africa (O’Rourke 1). The diamond engagement ring popularized in the 19th century symbolized innocence and durability (of marriage) when worn by a woman (Chesser 205). Ever since the Ancient Egyptians and Romans women “generally wore the ring on the left hand. Since most people were right-handed, they considered the left hand inferior. Wearing the ring on the left hand was thought to denote submission and obedience” (Chesser 205). Today, many of these murkier semiotic interpretations have been forgotten in exchange for ones of value and worth.

It wasn’t until the famed DeBeers diamond campaign of 1938 that the current image of the diamond ring we are familiar with emerged. In an effort to climb out of twenty years of low diamond numbers, the company hired advertising firm N.W. Ayer & Son to create a campaign. The firm reached out to Hollywood actresses and fashion designers to increase the visibility of the diamond engagement ring and combined those efforts with national advertisements. Between 1938 and 1941 DeBeers saw a 55% raise in sales, which was highlighted by the creation of the phrase “a diamond is forever” by N.W. Ayer & Son’s Frances Gerety. In 2007 it was recorded that 80% of American brides wear an engagement ring, a figure that because of this campaign has remained constant since 1965 (O’Rourke 2). In the midst of the diamond boom, religious wedding tradition changed as well. In “A Real Man’s Ring: Gender and the Invention of Tradition,” Vicki Howard traces the transition into the double ring ceremony that was popularized in the 1940s:

“Among Catholics and others prior to World War II, most

marriage vows took place with one wedding band. The Roman

Ritual called only for the blessing of the bride’s ring. [In 1944]

The Catholic journal concluded that as the groom’s ring was a

matter of custom and not legislation, “it is custom which will

govern the manner in which it is to be carried out”

(Howard 837).

This movement at its core makes the inequality of men and women fundamental to the institution of marriage. Its greater effect was defining the role of the ring as “custom”, which opened the doors for it to be interpreted as an economic opportunity.

Central to my curiosity with marriage is the emphasis placed upon costly symbols of love that seem to represent the economy of marriage instead of what it is supposed to be – an expression of love. It is important to note that these symbols are dependant upon their cost and would cease to hold power without knowledge of it. As Meghan O’Rourke states in “Diamond’s Are a Girl’s Worst Friend”, “Women are collectively attached to the status a ring bestows on them; otherwise more would demand some equal sign of commitment from their husbands” (O’Rourke 3). Through my ethnographic fieldwork it became clear that engagement rings reflect a woman’s self-worth and value, whether just to herself, or to the world. As Eric V. Copage noted from an interviewee in “Without This Ring, I Thee Wed”, the unequal distribution of engagement rings serves to highlight the fundamental message of an exchange that leans heavily to one side: “Just the symbolism of it is uncomfortable, because it’s almost like a down payment,” she said. “Or I guess it’s a way of proving that a man can be a provider”” (Copage 2). What is the necessity for conspicuous consumption in the field of marriage, or is it just that this concept has overflowed into every realm of modern life? Veblen would argue that indeed yes, it has. In modern day society, consumption has spread to effect our entire concept of “choice”, including those that we are told exemplify our individuality, but that in fact prove that we are forced to make a choice that was never ours to begin with (Ransome). It is important to note that money was not always given such a place in the proposal of marriage. Why then, have rings become just as adorned as the people who wear them? And why are these symbols given more of a voice than actions in the display of love? As Barbara Jo Chesser so aptly comments, “Lovers have not always given rings with valuable stones. Perhaps they feared that a monetary value would be places on the ring” (Chesser 205). My own dress up experiment showed me the social nature of visible consumption and proved that as Arendt says, the private (where feelings and emotions begins) is only preparation for and an extension of, the public stage.

This public stage however, seems to only allot space for female actresses. Without question, the engagement ring’s existence is dependant on men. They are both the purchasers and adorners of such rings, yet for ages have adamantly refused to wear them. While this has not always been the case, the oldest and most widely used symbol of the ring is not something that has caught on as universally with men as with women. Clearly there must be a reason for this? Here Chesser further analyzes the finding of one of her colleagues:

“Lacey (1969) found that except among medieval Jews of

Greece and Turkey, the man wore the engagement ring, not the

woman. Perhaps the man continued to wear the ring as long as

it symbolized power and authority. But when it became a

visible sign of bondage, and took on the meaning of obedience,

then the woman began wearing it (Thompson 1932)”

(Chesser 205).

I found a similar reaction brewing in myself when I wore my faux diamond ring on the streets of New York, ““Was the emergence of this opinion just a case of Stockholm syndrome, or some other unusual phenomenon strong enough to overtake even those who don’t wish to wear a ring? In some ways I did feel like a hostage to the ring, allowing it to modify my own image, personality and opinions to speak for itself” (Fauxfiancee, 3 August 2011). In fact many women agree that the engagement ring has a voice of it’s own, even though it may tell a different story to different individuals. The engagement ring does not act merely as a symbol and as Arendt concludes, meaning is not inherent in the object – it is always context specific. One requires an educated audience. But when the audience cannot be controlled, who is to say what education they have had? As a result, what reaction will it instill in them? O’Rourke states her own interpretation, which is shared by many “It’s a big, shiny NO TRESPASSING sign, stating that the woman wearing it has been bought and paid for, while her beau is out there sign-free and all too easily trespassable, until the wedding” (O’Rourke 2). Other than the unfair truth she states that men are free to act unhindered by this weighty symbol, engagement rings in everyday life do not seem to have much effect on men. Throughout the day of my dress-up experiment, I did not notice additional attention from any men; in fact I received less than I normally would. Perhaps this would not stand out as peculiar if not for the fact that women indeed noticed my ring time and time again.

Weaving in and out of these separate elements is one elemental idea within marriage symbolism, the clear dichotomy between the private nature of relationships and the objects that make them visibly public. Today the commodification of weddings and engagements does not only highlight the use of actual objects, it makes brides objects to adorn in themselves. Richard Sennett begs the question in The Fall of Public Man “Is there a difference in the expression appropriate for public relations and that appropriate for intimate relations?” (Sennett 6). Weddings have always needed to include an element of publicity to be made legal, even if it was only the presentation of a witness, but now this phenomenon has extended to affect the publicity of engagements as well. Through my experience on Brides.com and posing as a fiancée in the three-dimensional world, a proposal is perhaps the most widely shared story between fiancées. A fiancée’s storytelling and the questioning of her audience place the emphasis on the presentation of the engagement ring. Weddings and engagement rings are by no means the only methods of publicizing marriage. In The Meaning of Wife Anne Kingston argues, “The fact that power and wife are antithetical concepts extends more broadly to how women are seen in the public realm” (Kingston 21). So it can be observed that this lack of power is not contingent upon a woman’s status as a wife, but more her greater role of visibility in society.

Women are there to be seen, and keep up this appearance themselves, as John Berger notes. Much of the responsibility then can be placed on the shoulders of the woman, or fiancée who in my fieldwork I have noticed does not fight to break out of this mold. In my experience, even when brides make the conscious effort to embody what they are saying instead of their appearance, some still revert to speaking through “signatures” that proclaim the date of when she will or did marry and not a name, quote or other item of personal importance that is suggested on the site. As I have explained previously, my lack of experience and education in these matters served as a barricade to understanding them fully, but the widespread awareness of weddings makes nearly everyone part of the knowledgeable audience. Conspicuous rings and lavish weddings are commonplace in America today, so practically everyone is a knowledgeable audience, and publicity can in fact be gained without seeking the particular attention of the “bridal club”. Notably, the fact that rings are placed on a person’s hand – one of the most interactive parts of the body – only serves to heighten awareness of these adorned symbols. Brides experience life – whether it be collecting their change as I did, or grasping someone’s hand – through the eyes of their ring, so it is not absurd to assume that outsiders view them through the lens of their ring as well.

A woman’s presence communicates what she represents and from my experience delving into the online world of fiancées on the website, I interpreted that many fiancées wish to portray themselves first as part of a couple, second as a bride and somewhere near the end of the list as their own woman. Joanne Entwistle claims that the disembodied or mediated version of the self is just as important as the three-dimensional self, but what happens to a woman’s self-perception when her visible body is clearly absent? Aren’t engagement rings yet another way of disembodying and objectifying women? Upon a second glance these weapons may look strong, but in fact carry a powerless, subservient message. The focus and distraction on materialistic items throughout an engagement and ceremony cause one of Copage’s interviewees to wonder, “Without a ring, she reasoned, isn’t an engagement “just a conversation?” And when sharing news of her marriage plans with friends, she wondered, “What would I squeal over?”” (Copage 2). Not that you are getting married?

To many fiancées today it seems that consumption and objects are used to evaluate success and happiness, not an evaluation of one’s feelings of actual success and happiness. For others, however the clear distraction in the bridal world has caused them to return to a focus on relationships through a different lens, “”But then you take a step back and ask, ‘Why is this important to me?’“ she continued. “It’s a symbol that shows he is devoted to me.” Stepping even further back, she concluded: “He stood up in front of family and friends and a priest on a beach and exchanged vows with me. So, do I need the ring?”” (Copage 1). While these questions certainly lessen the necessity of an engagement ring, they can in exchange place all emphasis on the publicity of every other element. These symbols show that a woman’s fiancée is devoted to her, but whom does it show this to? More importantly, why does it matter? A separate force may be emphasizing the importance of these elements that is not in the couple’s control. For many years there has been an implied connection in religious circles between the observance of marriage rituals (and goods) and the longevity of a marriage (Chesser 207). There is clearly not one set of hands controlling the balance of power, the meaning or the expression of marriage symbolism.

Public displays of adornment have replaced public displays of affection, but more important than the word that’s changed, is the one that has not. Today publicity is more important than ever, and although the meaning of role women hold in society may be disputed, the fact that they must claim this role in public is not argued. As Sennett hypothesizes, today people are known through being seen (Sennett 11). I have found the constant most intriguing throughout my ethnography, that individuals do and should differ, but the way they make a space to be seen has stayed the same throughout history. More than sixty years ago, the claim was made tongue in check that diamonds are a girl’s best friend. This is not because diamonds are pretty and shiny when men are misogynistic and aging, it is because they act as insurance. If love, beauty and attraction can fade a woman needs something in her arsenal that cannot; here the engagement ring steps in. A diamond ring will not fade and neither will the multitude of ideas it symbolizes, whether they are insurance, worth or value. Jule Styne’s lyrics continue to say “time rolls on/and youth is gone/and you can’t straighten up when you bend/but stiff back/or stiff knees/you stand straight at Tiffany’s!” Ageism is relevant in both a woman’s career and personal life, and with the rising divorce rates some are as concerned with being traded in for a new model at home as they are at work. Again, the diamond engagement ring gives a woman power and insurance years after she says ‘I do’. Diamond rings are upgraded to reflect current trends when perhaps a woman cannot make her appearance relevant in other ways.

Vicki Howard discusses how “the groom’s ring only became “tradition” in the United States when weddings, marriage, and “masculine domesticity” became synonymous with prosperity, capitalism, and national stability” and this is certainly true (Howard 837). Everyone wants to stay relevant, and now equality is just as “trendy” as engagement rings. While inequality between men and women in relationships still runs rampant, a savvy woman can use the fact that she is the sole wearer of an engagement ring to her advantage; the publicity of the ring shares her message, whatever it may be. Men would be smart to embrace the engagement ring if they wish to extend their own space of visibility and power.

My ponderings on the topic changed over six weeks from ‘what does the engagement ring say?’ to ‘how does it say it?’ Throughout my ethnographic fieldwork online and in person certain findings caused this change, and there are still some questions that remain. What is the symbolism of a woman’s engagement ring to herself? What does size signify? What does the ring mean in private vs. in public to the rest of society? What does it mean within your own relationship? What is gained and what is lost through the wearing of an engagement ring? Although the importance of the diamond engagement ring may be a 20th century construction, its symbolism is ancient. Throughout the years its message has changed, but in some ways that too is as ancient as ever. Unfortunately the voice given by the engagement ring does not often share a positive symbolic message, but it is indisputable that the publicity an engagement ring gives the wearer bestows power upon them – and today they are women.

Works Cited

Arendt, Hannah. The Human Condition. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 1958. 199-208.

Berger, John. Ways of Seeing. London: British Broadcasting, 1977. 8-36. Print.

Chesser, Barbara Jo. “Analysis of Wedding Rituals: An Attempt to Make Weddings More Meaningful”. Family Relations. Vol. 29, No. 2, National Council on Family Relations, 1980. 204-9.

Copage, Eric V. “Without This Ring, I Thee Wed”. New York Times. April 2011. 20 July 2011.<http://www.nytimes.com/2011/04/17/fashion/weddings/17FIELD.html?scp=1&sq=engagement%20ring%20wedding&st=cse>.

Entwistle, Joanne. The Dressed Body. Oxford, New York. 2007. 93-104.

Goffman, Erving. The Presentation of Self in Everyday Life. New York: Anchor Books. 1959. 4-47. Print.

Gordon, Alexa. “Stand Still, Look Pretty: Letting Your Engagement Ring Speak For You”. Fauxfiancee. 3 August 2011. <https://fauxfiancee.wordpress.com/2011/08/03/stand-still-look-pretty-let-your-engagement-ring-speak-for-you/>.

Gordon, Alexa. “Into the Fiancée’s Den: Investigating the Digital World of Engaged Women”. Fauxfiancee. 20 July 2011. <https://fauxfiancee.wordpress.com/2011/07/20/into-the-fiancees-den-investigating-engaged-women-as-an-engaged-woman/>.

Howard, Vicki. “A Real Man’s Ring: Gender and the Invention of Tradition”. Journal of Social History. Vol. 36, No. 4, George Mason University Press, 2003. 837-856.

Kingston, Anne. The Meaning of Wife. Toronto: Harper Collins, 2004.

O’Rourke, Meghan. “Diamonds Are a Girl’s Worst Friend”. Slate Magazine. June 2007. 20 July 2011. <http://www.slate.com/id/2167870/>.

Ransome, Paul. Work, Consumption and Culture: Affluence and Social Change in the Twenty-First Century. Sage, 2005.

Sennett, Richard. The Fall of Public Man. New York: W.W. Norton & Company. 1976. 8-15. Print.

Styne, Jule. “Diamonds Are A Girl’s Best Friend”. Gentlemen Prefer Blondes. 1949.